The rise of lab-grown diamonds (or will your grandma’s gems be worth anything in the next 10 years)

One lazy spring Sunday, Nikolai and I were looking for an engagement ring. I should first explain, I was not raised with the idea that a diamond ring is a must but yet… but yet growing up I was surrounded by Hollywood movies, American TV-shows and expat girlfriends who all squealed at the idea of a big sparkling ring on their finger. Did I want one? Did I need one?

Even though Nikolai and I were already happily cohabiting for around 6 years at that point, the prospect of engagement and a future wedding left me all giddy and excited. “Ok,” I said to Nikolai, “let’s go and look at them bad boys”. And with these words we stepped into the plush interior of Gassans’s diamonds in Amsterdam. We were greeted by a perky assistant with a Russian accent. Politely she enquired about our budget, to which we replied: “Anything, let’s just take a look.” Our perky assistant perked up even more and came back with a tray full of sparkly rings. Now, at this point, it’s important to mention that I have quite long and thin fingers and love delicate understated jewelry. The big rings our assistant offered just didn’t feel “me”. So after each ring, I would comment: “Smaller please…”. “Smaller please.” Smaller, please”. Until there was barely any diamond visible at all. At this point, our now less than perky assistant turned to me and said in Russian: “Are you stupid? This man has no budget. You can have the biggest ring!”.

Suddenly, I was confronted by so many questions: Is this not just a ring? Is it a symbol of our commitment? Big love = big ring? But shouldn’t I just get what I like? When did a big diamond become a “thing”?

A bit of history

Anthropologists believe this tradition originated from a Roman custom in which wives wore rings attached to small keys, indicating their husbands’ ownership (lovely). In 1477, Archduke Maximillian of Austria commissioned the very first diamond engagement ring on record for his betrothed, Mary of Burgundy.

Even though the Archduke was the first to propose with a diamond ring, he was by no means a trendsetter. In fact, diamond engagement rings didn’t become popular until 1947 when De Beers, the British company that mined diamonds in South Africa, launched an advertising campaign. With the help of Hollywood stars and the slogan, “A diamond is forever,” diamond engagement rings skyrocketed in popularity.

The scarcity paradox

So what actually makes the diamond so desirable? Is it its rarity? The reality is that diamonds have never been scarce. For much of the 20th century, their supply was controlled by De Beers, which had more than 90 percent of the market. Since the 1990s other suppliers such as Alrosa have broken into the sector, but diamonds still benefit from being a so-called Veblen good — a luxury item whose price does not follow the usual laws of supply and demand — and whose appeal partly depends on their artificially high prices.

Over the past five years, the quality of lab-grown diamonds — first produced in the 1950s for industrial uses like cutting and polishing — has increased to the point where they have made their way into jewelry stores as gems set in rings, necklaces and earrings. Synthetic is a scientifically inaccurate term for a lab-grown diamond. Why? Because you can’t synthesize an element. Hold on. So we can grow a molecularly identical diamond in a lab? So many questions were running through my head. Can you really not tell the difference between a lab-grown and a mined diamond? Is a lab-grown diamond more sustainable, more ethical, and what about the investment aspect?

Meeting the diamond expert

Ok. This is as far as Google could take me. I had to meet with a real diamond expert. Olivia Smulders from Baunat Diamonds kindly agreed to explain to me about different diamond criteria and her take on lab-grown diamonds. But first things first, could Olivia tell which diamond is “real” and which one is a lab-grown gem?

I have to mention that I was researching and writing this article during Covid-19 times. This was the longest process and probably the most difficult piece I’ve written by far.

I presented Olivia with 3 rings: a stunning lab-grown diamond ring from Akind, an antique diamond ring that my mother-in-law gifted me and a little ring my mom passed on to me. Olivia examined all the rings in-depth and couldn’t conclusively say which diamond is which. Currently, sophisticated laboratory equipment used by an expert gemologist is required to make a positive identification. So far so good, we can apparently grow a molecularly identical diamond.

Olivia Smulders from Baunat Diamonds.

The rings (from left to right): a little ring my mom passed on to me, an antique diamond ring that my mother-in-law gifted me and a lab-grown diamond ring from Akind.

To be honest, the diamonds were too small for Olivia to make a good judgment call, but it was still fun to see if she could spot the lab-grown diamond.

The complexity of sustainability and ethics

One of the main topics of my conversation with Olivia was diamond sustainability and ethics. A major political effect of the diamond commodity chain, specifically at the mining level is “blood diamonds”. These are diamonds that are produced in war zones to finance civil wars. Olivia told me about the Kimberley Process which was created in 2003. This process is carried out by the manufacturers and it is a way to ensure the diamonds are not “blood diamonds”. Each diamond is given a certificate to prove its origin. Since its implementation, the world’s diamond supply is certified as 99% conflict-free.

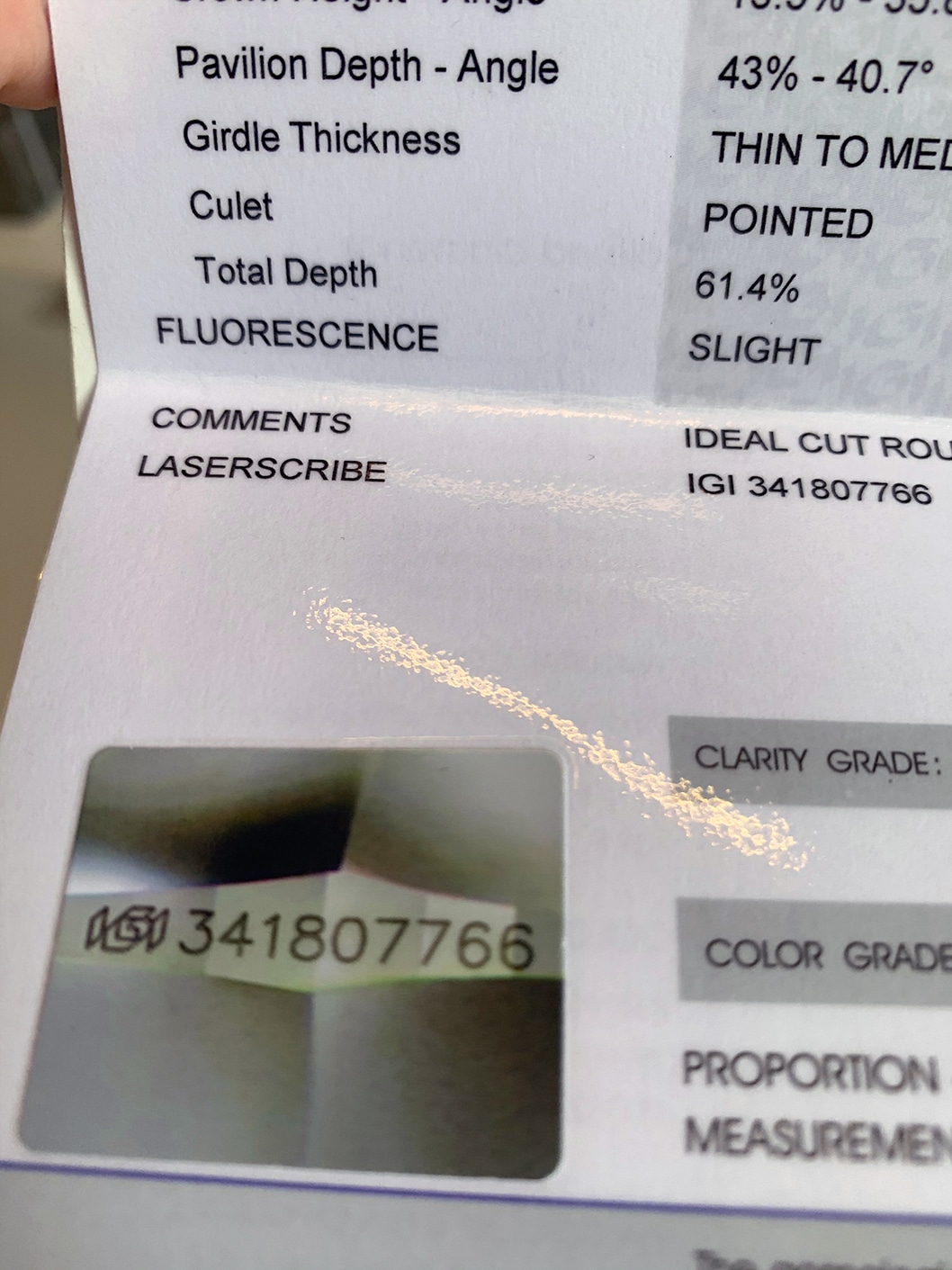

An example of how diamonds are graded.

Olivia showed me the laser inscription on each of their diamonds, a combination of letters and numbers etched in a diamond, most often on the stone’s girdle. These symbols serve as a unique ID that helps to identify a particular stone if needed to ensure this diamond has been mined ethically.

Number lasered on a ridge of a mined diamond. Usually on a gem larger than 1 karat.

Not only do diamonds and other gemstones have a history of human rights violations, but the mines themselves can also wreak havoc on the environment. Diamond mining has been linked to pollution of water sources used by local people due to acid mine drainage. This occurs when minerals from the mined rocks seep into the water supply. While still not a perfect system, small independent mines tend to be less detrimental to the environment and the mines can later be turned into a more sustainable venture, such as the former mines in Luc Yen, Vietnam, which are now rice fields. If you’re looking for the most sustainable (earth-mined) gemstones possible, you’ll want to look for jewelers in Canada.

But lab-grown diamonds are not without fault too. A distinct lack of transparency makes it difficult to source accurate data to compare the carbon footprints of mined and lab diamonds, but the energy needed to produce a lab diamond is significant. So, while neither lab diamond nor mined diamond industries are perfect, the wider environmental price from the latter is definitely higher.

However, the jewelry brand, Akind, works with the Diamond Foundry, a well-known diamond producer. They only use renewed energy (from solar panels) to grow diamonds in their lab. They’re in fact certified as a carbon-neutral diamond producer, so this takes care of the carbon footprint.

The quality of lab-grown diamonds is in general higher; 98% of all lab-grown diamonds created are of great quality and usable for its purpose, while approx. 80% of all mined diamonds that we dig up from our planet – causing harm to the earth, plants, animal life, etc. (regardless of the Kimberly Process) do not uphold the quality requested and are thus thrown away.

And a few nerdy facts (if you are into them): While mined diamond consumes more than 126 gallons of water per carat and produces 125 pounds of carbon for every single carat, a lab-grown diamond consumes just 18 gallons of water and emits 6 pounds of carbon for a single carat( 4.8% of what mined diamonds produce). Energy-wise, mined diamonds use 538.5 million joules per carat, while grown ones use 250 million. In total, air emissions on a single carat of a mined diamond are 1.5 billion times higher than those of a lab-grown one. Replacing this one mine’s annual diamond production with lab-diamonds could save the equivalent of about 483 million miles’ worth of auto emissions!

My lab-grown diamond ring from Akind.

Are diamonds still a good investment then?

Lab diamonds usually cost about 30% less than natural diamonds of comparable size and quality. But these diamonds are every bit as luxurious as their natural counterparts since their dazzling beauty and durability are the same. And this is where things get complicated.

As technology evolves and advances, the cost of creating lab-grown diamonds will decrease substantially and so the cost of the lab-grown diamonds at stores will also go down over time.

One element to look at for investment purposes is a rarity. No matter how much rough diamonds are unearthed from mines, there is a finite quantity as to how many diamonds are produced over 1-carat weight. Lab-grown diamonds, on the other hand, will be produced based on an order, meaning we can decide on whatever size, clarity and shape, and a lab will produce it, sort of like “made to order”. This will never happen to diamonds that come out of the earth. The other element to consider for diamond investment purposes is resale value and liquidity. Currently, there is no resale market for lab-grown diamonds, and in fact, there is no reason to have one. Why? Because most likely that by the time a person wants to resell his/her lab-grown diamond, new ones can be produced at much lower costs, so why buy a used lab-grown diamond when you can buy a new lab-grown diamond cheaper? Mined diamonds have a resale value, and in fact, the market for second-hand diamonds continues to grow. Diamonds are a commodity and like any commodity, their value can go down as well as up. On the whole, based on past performance, they go up – just very, very slowly. It’s virtually impossible to make a profit in the short term so it’s not just realistic to buy a diamond and expect to sell it for a profit after five years.

The pros and cons of lab-grown diamonds

Traditionally, diamonds have a strong cultural and social meaning. They are a sign of wealth and long-lasting love. The larger the diamond, the higher the social status of the owner. It can also be seen as a sign of greater love or commitment between couples. But to me, the new dawn of man-made diamonds is upon us. Perhaps, because I haven’t been brought up with the legacy of “The Diamond Ring”, the choice is simple: The sustainability, ethics, price and technology pros of a lab-grown diamond.

The pros:

- The first and most often cited benefit of lab-grown diamonds is their environmental sustainability. While this issue hasn’t been fully studied yet, it is generally accepted that it takes considerably less energy to grow a diamond in a lab than it does to dig it out of the ground. There is also no need to displace many tons of earth to create a lab-grown diamond.

- You can, with 100% certainty, know the origin of your diamond. The issue of conflict or “Blood” diamonds is very prominent in many consumers’ minds. While the real-world issue is not nearly as severe as many people believe it is (over 99.9% of natural diamonds are conflict-free), it is still reassuring to know that with lab-grown diamonds, you can be totally confident that your diamond did not support wars or child labor in any way.

- The price is another big benefit of lab-grown diamonds. Also, the savings go way up if you are looking for a colored diamond (natural colored diamonds are extremely rare and consequently very expensive).

- Lab-grown diamonds are new and exciting. To put it mildly, the jewelry industry has been around for a long time. It’s quite rare that something truly new comes around. Even though man-made diamonds have been around decades, we have only recently begun to see them reach a level of quality and size that is comparable with natural diamonds. Owning one can make you something of a trendsetter.

The cons:

- Just as lab-grown diamonds support more advanced economies, they also take jobs away from developing countries. When run responsibly, a diamond mine is a huge benefit to the economy of the host country. Oftentimes, these countries are impoverished, and the jobs and income that the mine brings can help elevate many people out of poverty.

- Lab-grown diamonds are not one-of-a-kind in the same way that natural diamonds are. Each earth-mined, natural diamond is a unique work of nature’s art. Lab-grown diamonds, on the other hand, are mass-produced in diamond factories. The mystery or glamour of the diamond may feel lost because of this.

In the end, we all have a choice to make. To me, unless you buy the diamond as an investment (and you REALLY should know what you are doing), the choice is a lab-grown diamond. Companies such as Akind not only make stunning lab-grown diamond jewelry at a fraction of the price but also give an old-fashioned esthetic a modern twist. A sort of diamond jewelry 2.0… which I personally prefer.

But the main conclusion of my investigation is choice. The rise of the lab-grown diamond gave us the ability to choose. To pick something according to our values, morals and financial abilities. And this, to me, is true freedom… to choose what’s right for you.

So earth mined or lab-grown? What is your choice?

No Comments

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.